I have a friend of 25 years who cannot get out of the house without using “fair and lovely” or as they call it now “glow and lovely”. She’s been using it for more than 20 years now. I remember her being very insecure because she was “dark” (still can’t understand what this means). She’s a beautiful woman. Has beautiful oily skin, wonderful sweat glands in her face that take care of the moisturizing, amazing curly hair, but to her beauty is being “fair”. I’ve been trying to understand this for over a decade: The reason why most of Asia and Africa has been gaslit to believe they are not adequately “fair” or “white”.

A type of black fungi, Cladosporium sphaerospermum, is doing radiosynthesis and creating energy using nuclear radiation in Chernobyl. Now, there is still more research that is to be done to be sure, but one thing is for sure. The Melanin in the fungi is protecting it from radiation. It neutralizes the radiation. I am talking about nuclear fission reaction radiation. MELANIN! The pigment that we were made to believe is the villain. The beauty industry has products that claim to reduce or stop melanin production. There are many fairness creams and whitening creams that “help” women achieve “fairness” by removing melanin from their skin.

Let us just stop this madness.

There is good reason why people in tropical climate have good skin. I am not talking about “glass skin”, “dewy skin” “fair skin” or “smooth skin”. Skin is an organ. The job of which is to protect us from any outside factors. People in tropics have more sweat glands and melanin that help in protecting them from harsh sun and heat.

There were cases in Kerala where a to-be bride was hospitalized due to nephrotic syndrome. When asked what was she using recently and regularly, she mentioned a skin whitening cream called Faiza beauty cream. Other similar cases were tracked and found that all were using this skin-whitening cream. It was found that the cream’s mercury content was 7,590 mg/kg, which is 7,590 times higher than the limit prescribed by the Minamata Convention on Mercury.

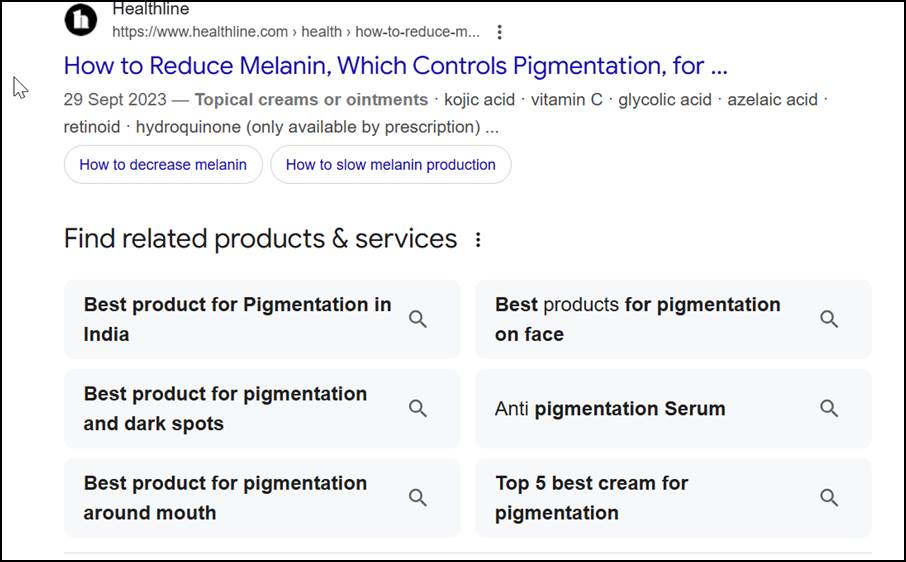

What’s worse? These creams are still available online.

I would love to live in a world where being called “black” is a compliment, because, with evidence, it is actually a compliment. It means your skin is working amazingly well. It is producing a natural barrier that protects you from radiation (UV or Gamma). Let us normalize and celebrate having pigment in our skin, because we are slowly destroying the God-given gift that is pigmentation by using ridiculous beauty products that feast on our insecurities.